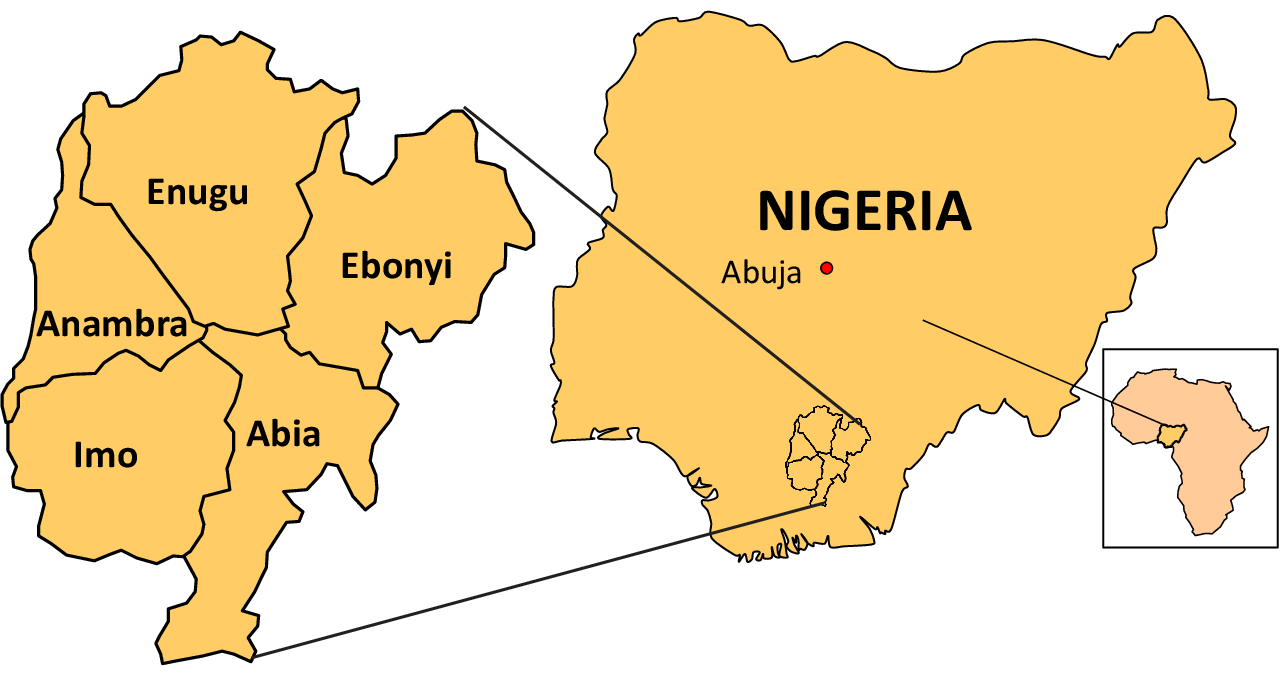

For years, the Nigerian government has established development commissions to address the economic and infrastructural challenges of different regions. The North East Development Commission (NEDC) was created to help rebuild areas devastated by insurgency, while the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) was set up to manage the unique environmental and economic concerns of the oil-rich South-South. More recently, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu signed into law the bill establishing the South-South Development Commission (SSDC) to further accelerate progress in the region.

Meanwhile, after years of delay and legislative bottlenecks, the South East Development Commission (SEDC) bill has finally been passed by the National Assembly. The Senate approved the bill on February 21, 2024, paving the way for its potential establishment. Yet, despite this progress, many still question why it took so long and whether the commission will receive the same level of funding and commitment as its counterparts.

A Long-Overdue Development

The push for a South East Development Commission is not new. The first attempt came in 2017 when the House of Representatives passed the bill, but it failed to gain Senate approval. In 2019, another version made it through both chambers of the National Assembly, only to be denied presidential assent by former President Muhammadu Buhari. Lawmakers and Igbo interest groups have since made repeated attempts to revive the legislation, yet each effort faced bureaucratic roadblocks until now.

Meanwhile, commissions for other regions moved swiftly through the approval process. The North East Development Commission was signed into law by Buhari in 2017, barely a year after it was proposed. The South-South Development Commission bill moved rapidly through the National Assembly before President Tinubu approved it in March 2025.

So, why did the South East have to wait so long for the same consideration?

The Political Angle: The Igbo Marginalization Debate

For many in the South East, the prolonged delay in establishing the SEDC fits into a broader narrative of political and economic exclusion. Since the end of the Nigerian Civil War in 1970, the Igbo have frequently complained of systemic marginalization in key areas such as federal appointments, infrastructure development, and political representation.

Unlike the North East, which had the Boko Haram insurgency as a justification for a commission, or the South-South, which contributes the bulk of Nigeria’s oil wealth, the South East has had no ongoing crisis that made the commission politically urgent for the government. Yet, supporters of the SEDC argue that historical neglect, poor federal infrastructure, and economic imbalance make the region just as deserving of targeted federal intervention.

Professor Nkem Okeke, a political analyst based in Enugu, notes, “The South East has some of the worst road networks in Nigeria, an underfunded industrial sector, and minimal federal presence. If development commissions are being established based on need, the South East should have been at the top of the list.”

Broken Promises and a Troubling Trend

Even when major federal projects have been announced for the South East, most remain uncompleted or have suffered years of delay. The Second Niger Bridge, a critical infrastructure project connecting Anambra and Delta States, was first approved in 2014 but faced years of stalled construction before its eventual completion in 2023. Even then, local residents complain that key access roads remain unfinished.

Similarly, the Enugu-Port Harcourt Expressway, which was flagged as a priority project under the Buhari administration, remains one of the most dilapidated highways in the country. Meanwhile, the NDDC and NEDC have successfully overseen large-scale regional projects, including road construction, health initiatives, and youth empowerment programs.

Chief Uche Nwosu, a business leader from Abia State, argues, “Whenever the South East is involved, it’s always one excuse or another. Other regions get development commissions and federal support, but when it comes to us, they suddenly start talking about ‘budget constraints’ and ‘procedural delays.’”

What Happens Next?

The passage of the SEDC bill is a positive step, but it is only the beginning. The real test lies in how the commission will be funded and implemented. Will it receive the same level of federal backing as the NDDC and NEDC, or will it be sidelined with inadequate funding and political interference?

A Test for Tinubu’s Political Strategy

President Tinubu’s administration has been keen on expanding political goodwill beyond his traditional strongholds in the South West and North. His approval of the South-South Development Commission was seen as a step toward fostering stronger alliances in that region. However, his handling of the SEDC will determine whether he is truly committed to addressing the developmental concerns of the South East.

As Nigeria moves toward the 2027 general elections, the success or failure of the SEDC could become a major talking point. If Tinubu wants to secure lasting political goodwill from the South East, his administration must ensure that the commission is not just another token gesture but a fully functional agency delivering real impact.

Final Thoughts: Will the South East Always Be the Exception?

The passage of the SEDC bill is a long-overdue victory for the South East, but skepticism remains. If other regions have secured dedicated agencies to address their unique challenges, the South East deserves nothing less.

Without full federal commitment, the SEDC risks becoming another underfunded and ineffective institution, reinforcing the long-held belief that the Igbo are treated as second-class citizens in Nigeria. If Nigeria truly wants to build national unity, it must abandon this selective approach to development.

For now, the South East has a development commission on paper. But will it have one in practice? Only time will tell.